Showcasing emerging Asian contemporary choreographers: Spot 2019

November 12, 2019 by David Mead

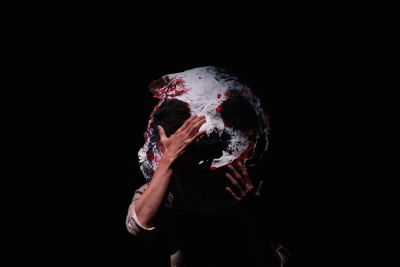

Kammy Lau and Ivan Chan in Speech by Henry Shum

Photo Alan Wong

Ngau Chai Wan Civic Centre Theatre, Hong Kong

November 1, 2019

David Mead

Expand the horizons of contemporary dance and provide performance opportunities for emerging choreographers is a very welcome aim. That is just what E-Side Dance Company (東邊舞蹈團) seek to do with SPOT Hong Kong (當代舞台), a gathering of local and overseas dance makers. SPOT 2019, part of the company’s wider annual Contemporary Dance Series, featured six short works, each around ten to fifteen minutes long, was certainly a varied evening.

I was most taken by the two duets. The closing piece: Distance (一隻手的距離) by Andy Lin (林則安) and Hsu Pei-jia (徐珮嘉) from Taiwan, the latter the only female choreographer of the evening, features a delicious dance by Hsieh Chih-ying (謝知穎) and Wang Yu-hung (王昱閎) of many and varied supports. The couple are almost in permanent contact. It’s largely slow-motion but with occasional momentary shifts in dynamic that constantly surprise. The subtle music and lighting helped the mood a lot, adding to that frequent feeling like the couple were floating in space.

in Distance by Andy Lin and Hsu Pei-jia

Photo Alan Wong

A second duet not only featured lots of quality dance but also plenty of food for thought. Speech (語) by Hong Kong choreographer Henry Shum (岑智頤) had Kammy Lau (劉燕珺) and Ivan Chan (陳俊瑋) in what appeared to be a conversation, although I frequently got the sense that what I was witnessing were her thoughts. He was there in the shadows, even if not there. A ticking clock in the soundtrack also hints at time passing, past or, given the text heard, towards a time when action is taken. The dance itself was full of innovative and very confident partnering and, when called for, super synchronicity

That text includes excerpts of interviews Shum did with his dancers concerning matters of identity, sustainability, dignity, resources and hardship faced by the whole dance performance industry in Hong Kong. Some of the points of view are quite personal, including how the industry tends to continue to label dance artists in particular ways. That is before we get to issues hierarchical relationship between investors, choreographer and dancers that can make it difficult for choreographers or dancers to make independent choices.

by Henry Shum

Photo Alan Wong

It’s not difficult to see a parallel here with the present Hong Kong social and political climate. ‘How do we get back our agency? Should we revolt?’ Shum asks. ‘Why are we not? And if we do, what are we willing to sacrifice?’ All pertinent but also all questions dance has asked everywhere at some point.

Most intriguing of the solos was the opening Snails (蝸牛) by Wang Yeu-kwn (王宇光). It opens with dancer Lee Yin-ying (李尹櫻) in a head mask vaguely resembling a snail, which she gradually breaks, it crumbling to the floor. A length of fabric that stretched into the wings can easily be seen as the trail that a snail invariably leaves on pathways.

Wang’s notes refer to people carrying personal heavy ‘shells’ as they try to contend with body and soul. Now unmasked, Lee’s twisted solo, often with circling limbs, certainly hints at that. It ends with a second performer in a second mask appearing. A thought that maybe we can never really shake or shell off, however much we try?

Being (存在) by Albert Tiong (張詠翔) from Singapore opens with silence. One man. One bench seat. To pulsing rumbles and pings, dancer Muhammad Sharul Bin Mohammed moves first with a fluid upper body. Lighting on the floor suggests a window and that he’s in a room by himself. It slowly gets more dynamic as he starts to shift around and move his seat but I’m not sure it ever revealed much about his self.

Photo Alan Wong

There was more than a dash of hip-hop influence in E(nd)rror by Korean choreographer-dancer Kwon Jae-heon. Overall, the dance lacked focus. The movement could have done with more clarity, as indeed could intent. A hand to his face was an interesting if unexplained recurring motif, and was a strip off a bid for freedom?

Finally, Phonate (鳴) by Hong Kong’s Wayson Poon (盤彥燊) featured the choreographer and a red chair. The sole idea seemed to be to make it appear that the single notes or harmonica chords heard were being created by his body. It had the sense of a starting point rather than a finished piece.